“I write because I don’t know what I think until I read what I say.”

― Flannery O’Connor

From <https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/315733-i-write-because-i-don-t-know-what-i-think-until>

There’s a lot of hype around journal-writing for authors.

Julia Cameron, in The Artist’s Way, calls journaling ‘Morning Pages’ and credits them with nothing short of creative miracles.

In the early twentieth century, authors and writers used journals the way fine artists use sketchbooks, to capture ideas, scribble down descriptions of people and things and settings, and to work out story ideas. These were much more workmanlike documents than the ethereal morning pages that Julia Cameron recommends.

But among those working uses, these writers also used their journals to keep a record of how their writing was progressing, and to work out and resolve story issues. Also, occasionally, their working processes were dissected and examined, too.

One of my favorite books of all time, The Kraken Wakes by John Wyndham, featured two radio writers who seemed to have notebooks attached to their left hands, in which they recorded enough salient detail in every minute of their days for one of them to describe events in the book (which stretched over a large number of years) just from notes and memory.

“Journals”, “diaries” and “notebooks” are sometimes interchanged for each other, but I think of them as three different types of documents, all with their own purposes.

Diaries

Diaries are chronological recordings of events in a person’s life. They may or may not contain reflections upon those events.

I keep a business diary that records observations and events concerning the publishing business I run. This is a professional document that I can use to supplement the bookkeeping and history of the company.

I also keep a log of personal events, in a rotating, perpetual diary that I keep inside OneNote. A perpetual dairy has, for example, every February 22nd’s events on the same page, so when you record this year’s Feb 22nd events, you can also look back at the events for each preceding February 22nd, underneath. It is a simple way of reviewing the years as they fly by.

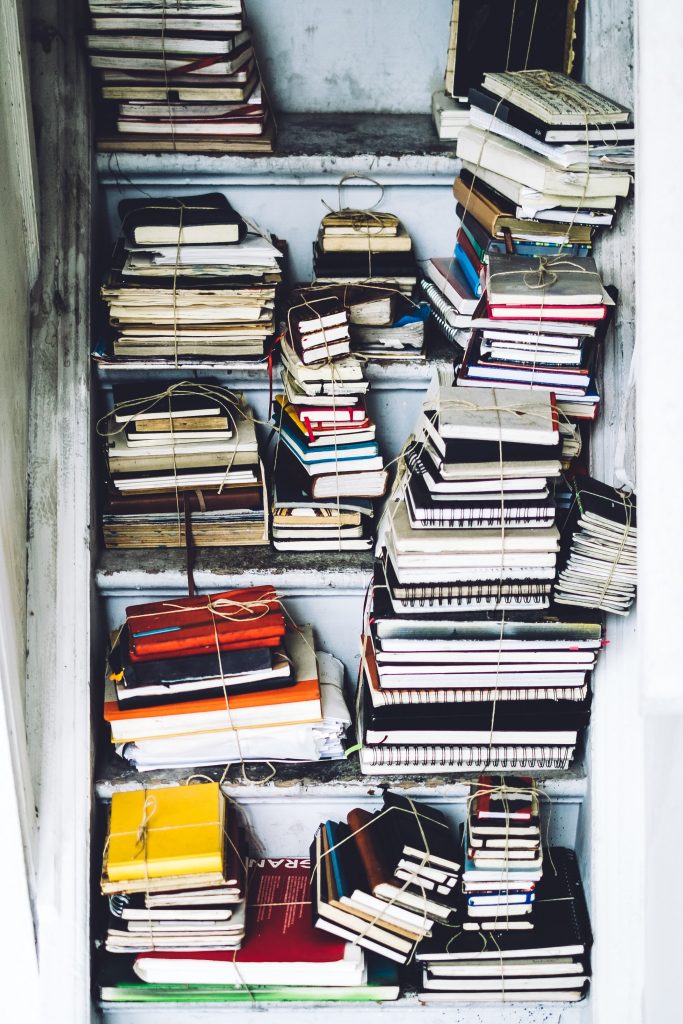

Notebooks

These are the workhorses of an author’s career. You can think of notebooks as being a catch-all that an author can use to develop stories and more. Like an artist’s sketch book, they contain snippets, random thoughts, clippings of images that appeal to you, inspiring quotes, story concepts you’ve scribbled while standing in a line, interesting phrases, interesting words.

While an artists would quickly draw an interesting face, you can quickly describe it, instead. Some of these captured sketches can sometimes be dropped virtually unchanged into stories.

You can use half a page to write a description of that funny-looking man drinking coffee on the other table, the one who is talking to himself. Or the sunset that is knocking your socks off as you and your partner drive back home.

Notebooks can be systematically mined for their gold later, when you’re actively building a new story.

They’re also repositories of background information, characters, research notes and more.

I use OneNote as an electronic notebook, and have dozens of individual notebooks for different subjects, including a notebook for every series I’ve written, which contains the series bible.

Journals

Journals are more intense examinations of aspects of your writing career. All of your writing career, including aspects that fall outside the actual writing itself–business aspects, work processes, people you meet, future projects that might come together…anything at all is fair game.

Unlike diaries and notebooks, journals are not simply a recording of facts. They’re a reflection of your thoughts. They’re where you work out stuff. Like Flannery O’Connor, I also don’t know what is going on in my mind until I write it down, and I use my journal to figure out what I’m really thinking. This is usually about issues, emotional problems, and more.

You might not want to journal every single day. I only turn to journaling when I have a sticky problem–especially those problems that make my guts roil, or make me angry–any issues with high emotional content become easier to deal with if you write out what you’re thinking about them, and figure out what is really going on.

One of the very best uses I’ve found for journaling lately has come about because I’m trying to maintain consistency over the long term, instead of the get-behind-and-now-catch-up feast/famine cycle I often fall into.

When I do find myself avoiding the writing I should be doing, I first get myself back to writing as quickly as possible. And once writing is done for the day, I journal about why I ducked the writing. Often, the reasons why I procrastinated (even a little bit) are buried. But once I’ve figured out what made me not open my manuscript and just start, I can make arrangements to ensure that particular category of interruption is avoided in the future.

For example, I had a day, recently, when my morning email delivered six different chores that needed to be done that day, including reviewing tax returns, line editing a story, etc. They weren’t five minute tasks, and I knew it. They nagged at the back of my brain, whispering that they would take time and effort, and my days are usually jammed already. I found myself dealing with those chores first, which sounds sensible, only I didn’t get back to writing at all that day.

Checking email first thing in the morning was tripping me up. And I thought I was immune to the lure of putting out fires before I’ve written for the day. My journal showed me otherwise.

Once I figured out what had happened, I switched things around. Now, I don’t even look at email until after my writing is done for the day.

—-

It’s not a requirement to use journals, diaries and notebooks, but they can enhance your writing in subtle and indirect ways. I find them invaluable. You may, too.

t.